Silvio Gesell believed that the two great economic evils were stagnation and inequality. He attributed stagnation to hoarding (the “retention” of money that slows circulation) and inequality to both hoarding and the payment of interest on money. His remedies were therefore twofold: demurrage (a carrying charge that makes money lose value if held, forcing it into rapid circulation) and interest-free credit.

From a Douglas Social Credit standpoint, Gesell’s take on monetary reform rests on a fundamentally flawed diagnosis and thus the remedies he proscribes are inadequate, in addition to being coercive and counterproductive.

1. Gesell’s Diagnosis Is Fundamentally Incorrect on a Deep Assessment of the Financial System’s Flaws and Only Partially Correct at Best from a more Superficial Assessment

Gesell’s central claim is that hoarding is the root cause of economic stagnation (and a major contributor to inequality). With the term ‘hoarding’, Gesell seems to mean holding on to money long-term with no intention of actually spending or investing it, but merely to earn interest as passive income (thereby removing money from active circulation).[1] This diagnosis is fundamentally mistaken for two reasons.

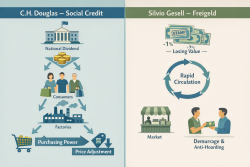

In the first place, and most fundamentally, Gesell completely misses the main structural defect that actually prevents the community from buying back what it produces, a defect which was identified by C.H. Douglas and encapsulated in his A+B theorem. In any modern economy, the total prices attached to goods and services (A + B) always exceed the total incomes distributed in the form of wages, salaries, and dividends (A). The difference (B) consists of overheads, depreciation, inter-firm payments, and other capital charges of a similar nature — costs that are not simultaneously distributed as purchasing power to the final consumer.

In other words, under the current financial system, not all costs are distributable as concurrent income because businesses must charge for real capital twice over: once to recover the financial capital that was expended on the manufacture or purchase of the real capital, and a second time for its use so that it can be replaced (depreciation charges). We often express this by saying that the financial capital is most often “prematurely cancelled” in capital loan repayments and is thus no longer available to meet the usage charges when these finally appear in consumer prices years and even decades into the future. Businesses thus charge the consumer more in the final products they produce than they have simultaneously distributed to consumers in the form of wages, salaries, and dividends. Let it be stressed that these capital charges are entirely legitimate under the existing rules of cost accountancy. As a result, the community as a whole can never buy back what it has produced unless additional purchasing power is continuously injected from outside the price system. This structural price-income gap is, on the Douglas analysis, the single greatest underlying cause behind economic stagnation and the lack of consumer buying power and it is due to a set of accounting conventions. The financial system has no built-in, automatic provision to compensate for it. Whenever the existing financial system fails to compensate for this lack with sufficient additional borrowing through a variety of exogenous palliatives, the economy stalls. Hoarding is not, therefore, the only cause behind economic stagnation nor is it even the prime cause.

In the second place, insofar as true hoarding can be a problem, a contributing factor to a lack of consumer demand, it is not always and everywhere a systemically aggravating phenomenon that requires deliberate correction in the way that Gesell supposes. Hoarding is potentially self-correcting in whole or in part through ordinary market behaviour. While some agents hoard, others routinely dishoard; i.e., they spend beyond current income by drawing on long-term savings built up in the past. The economy experiences genuine difficulty only when the current flow of new saving persistently exceeds the rate at which past savings are being spent back into the economy and there is no provision made to compensate for it (via new borrowing, for example). In that specific case there is indeed a shortfall of effective demand, but this is a de facto flow imbalance, not one that can be characterized as existing always and everywhere or necessarily. Such an adventitious imbalance, while a problem, is therefore not the systemic or inherent pathology that Gesell claims it to be. Incidentally, Douglas does explicitly acknowledge that savings and related phenomena like profit-making can indeed serve as secondary, exacerbating causes for the deficiency of consumer buying power. See, for example, his book: The New and The Old Economics in which five main causes are identified.[2]

Gesell thinks that hoarding is a much more important as a source of economic stagnation than it actually is because he appears to have assumed that the money supply is a fixed, permanent stock issued by the government and that banks merely act as intermediaries connecting savers and lenders. Both ideas are false. In reality, the great bulk of the money supply consists of bank credit that is created when private banks make loans or purchases and is destroyed when those loans are repaid or the purchases are sold back to the public. Money is not something that “circulates” in a closed loop; it is continually born and extinguished (destroyed) in the act of creation and repayment. This temporary, cyclical nature of the money supply is relevant to Gesell’s hoarding thesis because, in a debt-based money system in which the bulk of production and consumption occurs in the formal, monetized economy, money is not that easy for most people to hoard. First off, people have to live, which means they have to be continually spending money on accommodation, food, utilities, transport, healthcare and so on. Secondly, most people also have debts (mortgages, car loans, lines of credit, credit card debt, student loans), as do governments and businesses. Debt-servicing charges and taxes continually swallow up large sums of money which are then not available to be hoarded. In general, Gesell seems to have underestimated or neglected altogether the many factors that actively incentivize, if not demand, continual spending as well as dishoarding. Money under the existing system is already perishable, not imperishable as Gesell supposed.

In sum, the Social Crediter would say that Gesell’s hoarding diagnosis is flawed because it exaggerates a manageable and partially self-correcting tendency to save money into the central problem of economic life, while entirely overlooking the structural purchasing-power accounting gap that is the real deep source of both stagnation and the chronic need for additional debt (with interest charges attached) to compensate for it. The compound interest charged on that debt and mainly in favour of financial institutions then centralizes wealth, privilege, and power in the hands of the few, the owners of the system, thus contributing to gross inequalities.

As far as Gesell’s belief that the charging of interest is the other key factor behind economic stagnation and especially economic inequality, I want to make it clear that, contrary to what many suppose, interest is not the main cause behind the price-income gap and that it is not even involved as a special cause that is any way different in kind from what might be ascribed to the profit-making of any businesses. The debt virus hypothesis, i.e., that interest on debt requires even more debt to pay the interest (because the banks don't create the interest they demand) is, to a large extent, false. Banks also spend money (which they create) into the economy whenever they pay for raw materials, operating expenses, wages, and so on. They also distribute part of their profits in the form of dividends. These bank injections of credit help to offset a significant portion of the interest charges. Only that portion of interest representing retained profit (which, in the case of the banks, is not inconsiderable) might contribute to a gap, but that the principle behind that holds true in the case of any business. Now, it is correct that interest can and does have a centralizing effect, but most of this is due to long-term compensatory debt which is used to fill the recurring price-income gap. Interest, especially compound interest, charged on debt that is used to fill a gap that should not exist might be defined as usurious by its very nature. If that gap were filled as Douglas proposed, via the issuance of compensatory debt-free consumer credits, the additional government, business, and consumer debts would not be necessary and the centralizing effect of the resultant interest charges would be entirely obviated. So what comes first, the chicken or the egg? Douglas would argue that it is the chicken, i.e., the debt, that comes first. Eliminate the debt and you eliminate the interest. Eliminate the interest and you eliminate the kind of economic inequalities which stem from usurious interest charging.

2. Gesell’s Remedies Are Flawed and Counterproductive

Because his diagnosis misses the real economic problem, the structural price-income gap, and is only partially correct in reference to the more superficial problem of hoarding, the remedies that Gesell proposes miss the mark and are actually likely to cause additional problems of their own.

To begin with, demurrage cannot address the core economic problem, not even by a side wind, because it only accelerates the flow of money; it does nothing to fill the recurring price-income gap that is caused by the A+B factor.

Because money is not permanent, but is created and destroyed by the banking system and because money is used to catalyze production and to distribute income for consumption, the two main accountancy cycles that dominate economic life, the creation and destruction of money on the one hand, and the creation and destruction of prices via the spending of purchasing power on the other, are linked. The money created by the one cycle is the source of funds for liquidating prices in the other. But, as we have seen in examining the A+B factor, the two cycles are also fundamentally out of sync under the existing financial system. That is, as money is created and destroyed in the banking accountancy cycle, costs and prices are being generated faster than incomes can be distributed in the price system’s accountancy cycle. This is due fundamentally to the fact that not all costs are distributable as concurrent income.

Now, a policy like demurrage can speed up these cycles to be sure, but increasing the velocity of money can do nothing by itself to close the A + B gap. It merely forces the existing volume of money through the same accountancy cycles at a higher frequency. Every production cycle will still be generating prices (A + B) faster than it distributes incomes (A). The result is not an increase of purchasing power relative to corresponding prices, but a more rapid recurrence of the same deficiency. No amount of increased velocity can compensate for a system that systematically fails to distribute sufficient purchasing power in the first place. In other words, even with perfect circulation (no hoarding), aggregate price generation will exceed the rate of aggregate income distribution. The price-income gap is structural (mathematical), not behavioural or psychological.

Demurrage could, at best, have relevance only in the narrow case where new saving really does persistently exceed the rate at which past savings are being spent and where there is no ‘naturally-motivated’ compensation occurring — i.e., a deficiency that could be described as being the effect of “hoarding.” In that limited circumstance, demurrage might appear to help restore balance to the circular flow by penalising the retention of money, but at what cost and is the cost worth it? And, are there other, better ways of dealing with a deficiency of consumer buying power that is caused by hoarding?

We are dealing here with the law of unintended consequences. Yes, demurrage could incentivize dishoarding, but it is also likely to cause fresh and serious distortions. To begin with, it is an indiscriminate tax on the mere holding of money, regardless of purpose. Low-income households depend on modest reserves for emergencies, health care, and education. Families save for homes, retirement, and children’s futures. Businesses hold liquid balances for inventory, equipment replacement and smoothing out cash-flow issues. By eroding every unspent balance uniformly (most of which do not even qualify as hoarding in the strict sense of that word), demurrage discourages prudential foresight across the entire society. It penalizes individuals and businesses for provisioning for themselves. Douglas rightly called demurrage a type of “disappearing money” system that involves “the heaviest form of continuous taxation ever devised.”[3] Unlike conventional taxes that can be targeted or progressive, this levy operates as a relentless, blanket charge on liquidity, disproportionately burdening those individuals with the least flexibility to adjust without suffering real economic harm. And what effect on economic functionality in general might it have when individuals and organizations (institutions and businesses) cannot save without being penalized? Demurrage is likely to incentivize economic activity that is not in line with the true purpose of economic association, thus introducing inefficiency, waste, and friction.

This last point is incredibly important, so we might take some time to flush it out further. According to Douglas Social Credit, the true purpose of an economy is to deliver the goods and services actually required and desired by the community so they can survive and flourish and to achieve this with the least possible expenditure of human labour and physical resources. But demurrage is likely to interfere with the decisions that economic agents need to make in order that this true purpose of economic association might be optimally fulfilled. This is because demurrage treats spending as an end in itself rather than as a means to human well-being, and is not so concerned, therefore, with what the money is spent on. When demurrage is in play we can ask: does this or that instance of spending reflect the independent will of the consumer, what he would really be spending money on if he was not labouring under demurrage? It tends to skew things in a quantitative rather than qualitative direction because its main objective is to overcome what it perceives as circulation blockages in order that the economy cannot avoid stagnating. Thus, while demurrage may produce a surge in the rate of transactions, it does nothing by itself to ensure that the goods and services that are truly desired are being delivered in the most efficient manner and is even likely to induce patterns of production and consumption that are at odds with the fulfilment of the economy’s true purpose.

Douglas succinctly captured the error: “The theory behind this idea of Gesell’s was that what is required is to stimulate trade — that you have to get people frantically buying goods — a perfectly sound idea so long as the objective of life is merely trading.”[4]

But the object of life and the object of the economy are not mere trading for the sake of trading. The object of life is not trading at all, but self-development and through self-development the achievement of transcendence. The object of the economy is trading for the sake of delivering what people need to survive and flourish with the least amount of labour and resource consumption. In other words, whereas Gesell is myopically concerned with circulation as an end in itself (as if solving that particular issue was a sufficient condition for solving all other economic problems), Social Credit treats this question of circulation as a means to an external, non-immanent end: the efficient delivery of goods and services to consumers.

The whole psychology of demurrage as means to induce spending is thus at odds with the true purpose of the financial system and of the economy as a whole. Indeed, all such schemes that use money to “stimulate”, “cajole” or psychologically manipulate people into spending or engaging in any economic activity transform the monetary system from a neutral record of economic facts into an instrument of behavioural control. It is forcing people to do things they wouldn’t otherwise do in order to make the money system work, instead of making the money system work by reforming it appropriately so that it reflects what people really want to do. The silent false assumption is that the money system and its needs should come first ahead of the really economy and its needs. The embodiment of this incorrect philosophy in monetary policy can only cause people’s economic activities to deviate from a direct and simple fulfilling of the true purpose of economic association towards the fulfillment of another purpose: making the money system work. As Douglas once put it:

“All these schemes are based on the assumption that you have to stimulate something or other. They are an attempt to produce a psychological effect by means of the monetary system. In other words, the monetary system is regarded not as a convenience for doing something which you decide yourself you want to do, but to make you do something because of the monetary system.

I am not going into Social Credit technique to-night; I merely want to repeat that our conception of a monetary system is that it should be a system reflecting the facts, and it should be those facts, and not the monetary system that determine our action. When a monetary system dictates your actions, then you are governed by money, and you have the most subtle, dangerous and undesirable form of government that the perverted mind of man—if it is the mind of man—has ever conceived.”[5]

There are also more practical, incidental risks that could flow directly from imposing a Demurrage psychology on people, especially if the demurrage rate is relatively high. To cite one example, Douglas warned that artificially hurried spending bears some potential to degenerate into unstable, panic-like behaviour:

“In fact you have exactly the same state of affairs as existed at the time of the stupendous German inflation of the mark. When a waiter received payment in millions of marks he hardly waited to throw down his napkin before dashing out to buy something, because the value was disappearing so rapidly.”[6]

Some of Gesell’s contemporary followers have suggested that demurrage revenue could be used to finance a dividend for all citizens (which would be a more and more important use of such funds given the realities of increasing technological labour displacement) and/or to finance public works. Whatever benefits this might bestow on the population, it is necessary to emphasize that a demurrage-funded dividend or public works system cannot close the A + B gap itself. Like all taxes, demurrage funding would merely redistribute a secondary flow of funds that leaves both the structural A+B deficiency and its need for fresh additional purchasing power to balance it out untouched. No matter how you slice it, you cannot make an insufficiency sufficient by redistributing it. Demurrage is not adding more money when more money is, in fact, periodically needed, it is just shuffling it around.

As far as Gesell’s remedy of interest-free credit is concerned, it likewise fails to address the core problem with the financial system. Even if loans were issued without interest, the necessity to borrow would remain so long as aggregate incomes fall short of aggregate prices. Credit—interest-bearing or interest-free—enters the economy as debt that must ultimately be repaid, and repayment withdraws purchasing power from circulation, leaving the underlying A+B gap unresolved. In other words, interest-free credit may remove one factor that can contribute to unjust inequality, but it does not eliminate the systemic compulsion to incur debt that generates both economic instability and the concentration of wealth in the hands of financial institutions. Beyond that, financial institutions must charge something, whether in the form of interest or service fees, in order to cover their costs and to make a legitimate profit if and when they do a good job in serving the public interest. While usury, properly defined as economic rent-taking in lending, should be abolished and would be by the side-wind of Douglas’ remedial proposals, eliminating interest or its equivalent entirely would render banking impossible, with great fallout for the economy if loans cannot be made because legitimate fees to cover their expense of such loans cannot be charged.

3. Douglas Social Credit Solves the Financial System’s Core Problem Directly, Coherently, and Without Coercion

In contradistinction to Gesell’s demurrage proposals, Douglas Social Credit addresses the structural purchasing-power gap that Gesell missed and does so at its source.

The National Dividend distributes additional purchasing power debt-free to every citizen as a birthright, directly bridging the gap between aggregate incomes (A) and aggregate prices (A + B). The Just Price / Compensated Price mechanism lowers the effective price of goods to the consumer by the same proportion as artificially inflated financial costs exceed real costs, again without creating new debt.

These measures are dynamic: if past savings temporarily exceed current spending, the dividend or price adjustment can be moderated; if the gap widens, they can be increased. The system therefore maintains equilibrium without penalising anyone for holding money, without coercing behaviour, and without turning the monetary mechanism into a tool of psychological manipulation and behavioural control. As far as hoarding is concerned, since the DSC proposals are to be implemented within the context of “the minimum employment necessary” as opposed to the present policy of full employment, the vast majority of people, upon receiving their dividends would be inclined to spend them immediately in order to maintain a basic standard of living or to otherwise supplement their standard of living (which is the very purpose for which they would be issued). Since the compensated price discounts are only issued if and when a sale is made, that use of compensatory money is even more directly tied to consumption and is thus not available to be hoarded in the first place.

Now, it is worth re-emphasizing that because the dividend and the compensated price are debt-free, they eliminate the need for interest-bearing bank credit issued to governments, businesses, and consumers to fill the gap. The upward flow of interest that currently concentrates wealth in the hands of the financial elite is thereby cut off at its root. Equity is enhanced, not by punishing savers, but by removing the artificial scarcity that forces most people into chronic debt in the first place.

Conclusion

Gesell’s diagnosis mistakes a secondary and partially self-correcting phenomenon (hoarding) for the central defect of the current monetary system (alongside interest on debt), while entirely overlooking the structural A + B gap. His main remedies — demurrage and interest-free credit — necessary fall short and even create and compound other problems. Demurrage accelerates the deficiency it claims to cure, penalises necessary saving, coerces behaviour, and risks unstable spending patterns, while interest-free credit addresses only one consequence of debt without eliminating the structural compulsion to borrow in order to bridge the income–price gap. Both remedies leave the real mechanisms of stagnation and power centralisation untouched.

Douglas Social Credit, by contrast, identifies the structural purchasing-power gap as the main economic problem, fills it directly with debt-free credit distributed as a dividend and a price adjustment, preserves the legitimate functions of saving, stabilises the economy, ensures a more equitable distribution of wealth, and aligns production with the true purpose of economic activity: the delivery of goods and services to consumers with the least possible human effort. It is therefore not merely a more effective policy; it is a policy that is both practically sound and ethically consistent with the dignity and freedom of the individual.

A large part of the enduring appeal of Gesell’s proposals in certain quarters appears to lie in the incorrect mental model of the financial system that Gesell—and many of his followers (who should know better by now)—appear to have taken for granted: that money is a permanent, government-issued stock whose movement alone sustains economic activity and that the banks are lending funds that have been deposited with them by savers. This makes hoarding and interest-taking seem like the obvious villains behind stagnation and inequality. Within this diagnostic context, it is easy to see why demurrage and interest-free credit might feel compelling: they offer a direct, visible lever to “unstick” the economy and redistribute wealth. Once people understand the financial system in terms of the bank-credit model—where most money is continuously created and extinguished through lending and repayment—and in terms of the inherent imbalance in the price system, due to standard cost-accounting conventions (i.e., that prices and costs are generated faster than incomes are distributed), the intuition that hoarding and interest are driving economic dysfunction collapses. The real problem is the systemic A + B accounting gap and the accompanying endemic deficiency in consumer buying power, not the secondary phenomena of interest or delayed spending. Gesell’s ideas resonate because they seem simple, moral, and actionable, but they miss the root structural causes of stagnation and inequality and, as we have shown, are likely to generate their own set of difficulties in terms of economic inequality and dysfunction.

-----------------

[1] When Silvio Gesell talked about hoarding, he wasn’t condemning the ordinary holding of money for everyday transactions or short-term liquidity; he meant the long-term accumulation of money that is deliberately kept out of circulation, often to earn interest or profit, without any intention of spending or investing it productively. This type of hoarding, according to Gesell, reduces the velocity of money, creating a drag on the economy, because money that could be used for trade, production, or wages sits idle instead. In his view, ordinary cash balances for practical purposes aren’t “hoarding,” but wealth accumulated purely to earn passive income—like interest or capital gains on money that never circulates—is what disrupts economic flow.

[2] C.H. Douglas, The New and the Old Economics (Sydney: Tidal Publications, 1973), 15:

Categorically, there are at least the following five causes of a deficiency of purchasing power as compared with collective prices of goods for sale:---

- Money profits collected from the public (interest is profit on an

intangible). - Savings, i.e., mere abstentation from buying.

- Investment of savings in new works, which create a new cost

without fresh purchasing power. - Difference of circuit velocity between cost liquidation and price

creation which results in charges being carried over into prices

from a previous cost accountancy cycle. Practically all plant char-

ges are of this nature, and all payments for material brought in

from a previous wage cycle are of the same nature. - Deflation, i.e., sale of securities by banks and recall of loans. There

are other causes of, at the moment, less importance.

[3] C.H. Douglas, The Approach to Reality (London: K.R.P. Publications Ltd., 1936), 9.

[4] C.H. Douglas, The Approach to Reality (London: K.R.P. Publications Ltd., 1936), 9.

[5] C.H. Douglas, The Approach to Reality (London: K.R.P. Publications Ltd., 1936), 9-10.

[6] C.H. Douglas, The Approach to Reality (London: K.R.P. Publications Ltd., 1936), 9.